We have just read in the last chapter that the Hyūga-Masamune was originally called Katada-Masamune. This has nothing to do with this chapter but should serve as bridge to the protagonist of the following legend who was a certain bushi called Katada Matagorō (堅田又五郎). Katada was a place on the southwestern tip of Lake Biwa,*1 who was an important traffic junction and a fishing centre at all times. The Ōnin War (Ōnin no ran, 応仁の乱) which broke out in the first year of Ōnin (応仁, 1467) in Kyōto soon spilled over into the neighboring provinces (Katada is about 20 km linear distance to Kyōto). The lords of the numerous smaller fiefs in this area used the turmoils of the war to get the local supremacy. The most outstanding of this so-called Katada-shū (堅田衆) or Katada-shoji (堅田諸侍) called groups was Katada Hirosumi (堅田広澄), a vassal of Hideyoshi who was in the controll of lands worth 20,000 koku.

Katada Matagorō lived somewhat earlier, around the end of the Ōnin War which lasted ten years. He was one day on the way at the foot of Ibukiyama (伊吹山) in Ōmi province, accompanied by a carpenter. It was already late and to avoid walking in the dawn, they stepped on it. But it didn´t help and at falling night they where middle of nowhere in a gloomy wood. Without warning the carpenter turned into a horrifying figure and attacked Matagorō with his teeth bared. Matagorō was surprised for a second but drew his sword – a blade of Bizen Nagamitsu (備前長光) – and thrusted at the creepy carpenter, or at least what was left of him. Matagorō was lucky that he had his sword thrusted through the belt and not wearing it over the shoulder like it was common for travellers.

With a metallic “pling” the blade cut in half the plane (kanna, 鉋)*2 the carpenter had raised as defence and suddenly the monster vanished into thin air. Due to this incident, Matagorō called his sword Kannagiri-Nagamitsu (鉋切り長光), lit. “plane-splitter Nagamitsu.” This incident quickly made the rounds and eventually reached the Rokkaku family (六角),*3 castellans of Kannonji (観音寺城) and military governors of southern Ōmi province, who without forder ado ordered the confiscation of the sword. The exact circumstances of the involuntary handing-over or why a simple bushi bore a blade of the famous swordsmith Nagamitsu are not known. However, records of the Rokkaku family say that the piece became at the latest in the Eishō era (永正, 1504-1521) the favourite sword of Rokkaku Ujitsuna (六角氏綱, 1492-1552).

Ujitsuna had no son and heir and so Yoshikata (義賢, 1521-1598), the eldest son of his older brother Sadayori (定頼, 1495-1552) had to succeed as head of the family as was the law at those days. And consiquently the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu went into his possessions. Some years later Yoshikata felt ill and once again, no one of the fief´s physicians was able to cure him. A worried vassal of the family visited a fortuneteller (uranai-shi, 占師) who said: “I see that the illness of your lord has something to do with a certain Matagorō and that he is under a curse of a killed carpenter. To solve the curse, one has to die for the sick person and further, the sword has to be offered to the Hyakusai tempe (百済寺, which lies to the east of Lake Biwa).”

The hard lot was assumed by Namazue Sadaharu (鯰江定春), lord of Namazue Castle (鯰江城) of the same name. Sadaharu came from a branch of the Rokkaku family and amid countless praises and expressions of thanks he was buried alive at the temple grounds of the Hyakusai! But the fortuneteller was to be right because Yoshikata´s condition was better and better every day after this gruesome ceremony.

At that time, the tension of impending war grew in the air and one of the main routs to Kyōto leaded through the southern part of Ōmi province. The political and military power of the Ashikaga shōguns was now completely destroyed and a kind of power vacuum had arosen in the course of which Oda Nobunaga saw his opportunity of attaining a supremacy. With Ashikaga Yoshiteru (足利義昭, 1537-1597) – which he installed later as “puppet shōgun” – he marched towards Kyōto in the eleventh year of Eiroku (永禄, 1568), opposed by the army of Yoshikata. But resistance was futile, the castle of Kannonji was besieged and surrendered, and Yoshikata was able to escape to the mountain region of Kōga (甲賀) in the southeast of Lake Biwa.

It is likely that the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu went into the possessions of Nobunaga when Yoshikata surrendered the castle because some years later, on the 24th day of the sixth month of Tenshō seven (天正, 1575), he presented it together with a famous tea bowl called Shūkō (周光) to his vassal Niwa Nagahide (丹羽長秀, 1535-1585) who served him loyal since his youth. From Nagahide the sword went under not nearer defined circumstances to Gamō Ujisato (蒲生氏郷, 1556-1595), lord of Aizu-Wakamatsu Castle (会津若松城) in northern Japan. Another possibility how the sword could have came to Ujisato would be the following: Ujisato´s father Katahide (賢秀, 1534-1584) was castellan of Ōmi´s Hino Castle (日野城) and a retainer of Rokkaku Yoshikata who was back then in control of the lands around Kannonji Castle where also Hino Caste was located. When Yoshikata holed up in the mountains of Kōga, his retainer Katahide was not willing to surrender Hino without resistance to Nobunaga.

Well, Nobunaga sent thereupon Katahide´s brother-in-law Kanbe Moritomo (神戸盛友) (who was adopted into the Gamō family) as negotiator and Katahide finally gave up. Maybe Nobunaga gave Moritomo the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu as a kind of bribe and attempt of persuasion. The common tradition of the passing on of the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu says that the sword went from Ujisato to Toyotomi Hideyoshi who presented it to Tokugawa Ieyasu, who on the other hand bequeathed it to his son Hidetada. But things were somewhat different. When the third Tokugawa-shōgun Iemitsu (家光, 1604-1651) visited Ujisatos´son Tadasato (忠郷, 1602-1627) in his residence on the 14th day of the fourth month Kan´ei one (寛永, 1624), he received as a welcome gift a tachi of Bungo Yukihira, a wakizashi of Sōshū Sadamune (相州貞宗), and the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu. Additionally it should be said that Tadasato´s mother Furihime (振姫) was the third daughter of Ieyasu, i.e. the aunt of Iemitsu. And so the Kannagiri came into the possession of the Tokugawa family.

Iemitsu´s sister Tamahime (珠姫, 1599-1622) was married to Maeda Toshitsune who was already introduced in the chapter about the Ōtenta-Mitsuyo. Their daughter Kametsuru married in Kan´ei three (1626) Mori Tadahiro (森忠広, 1604-1633), son of Mori Tadamasa (森忠政, 1570-1634). Tadahiro was installed successor of Tadamasa and future lord of the Tsuyama fief. As a wedding present Tadahiro received a wakizashi of Taima Kuniyuki (当麻国行) and the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu. But their luck did not hold because Kametsuru died four years after the wedding at the age of 18, and Tadahiro only three years later with 30, even before his father Tadamasa. So Tadahiro´s younger brother Nagatsugu (長継, 1610-1698) became the official successor of Tadamasa. Nagatsugu was granted with a very long life and when he retired in the second year of Enpō (延宝, 1674) he presented the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu together with a calligraphy to Ietsuna (家綱, 1641-1680), the son of Tadamitsu and the fourth Tokugawa-shōgun.

Shortly thereafter, in the ninth month of Enpō six (1679), the sword got an appraisal (origami, 折紙) of the Hon´ami family designating it a monetary value of 25 gold pieces. The sword was handed down from shōgun to shōgun until the end of the Edo period and already the work Hon´ami Kōetsu Oshigata (本阿弥光悦押形) published in the eighth year of Keichō (慶長, 1603) notes “shōgun ni te” (将軍ニ而, lit. “at the shōgun[´s place]”). That means also that the oshigata of the blade was drawn in the residence of the shōgun. But at the time of the big Kantō earthquake from 1923 the sword was together with the Konotegashiwa-Kanenaga in the residence of the Mito-Tokugawa branch in Edo´s Mukōjima district (向島) and suffered therefore a fire damage (yake-mi, 焼け身) which meant the loss of its tempering.

The then head of the Mito-Tokugawa family, marquis Tokugawa Kuniyuki (徳川圀順, 1886-1969) immediately informed the owner of the blade – the 17th shōgun prince Tokugawa Iemasa (徳川家正, 1884-1963) – and asked him to let him the blade. Three weeks later Iemasa agreed and by intercession of Kuniyuki, it received in 1949 the status of jūyō-bunkazai even it had no longer its original tempering.

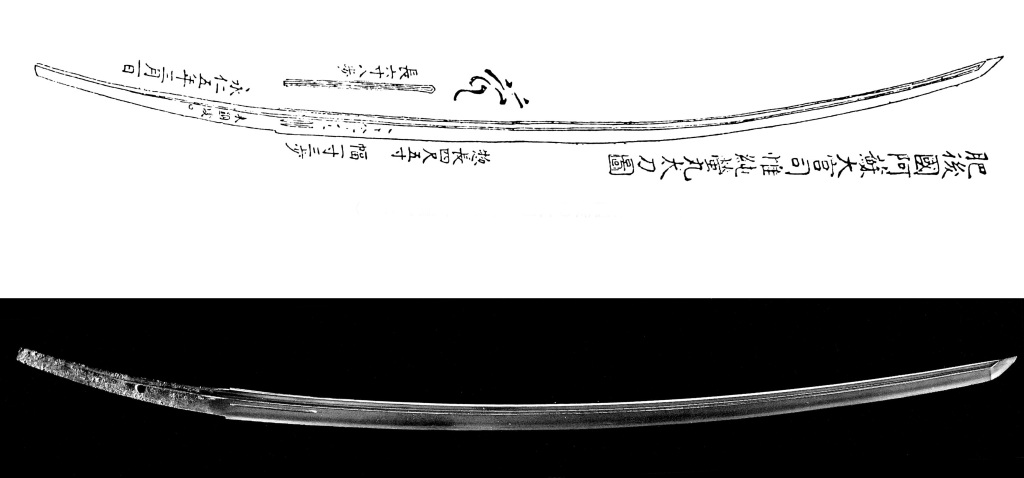

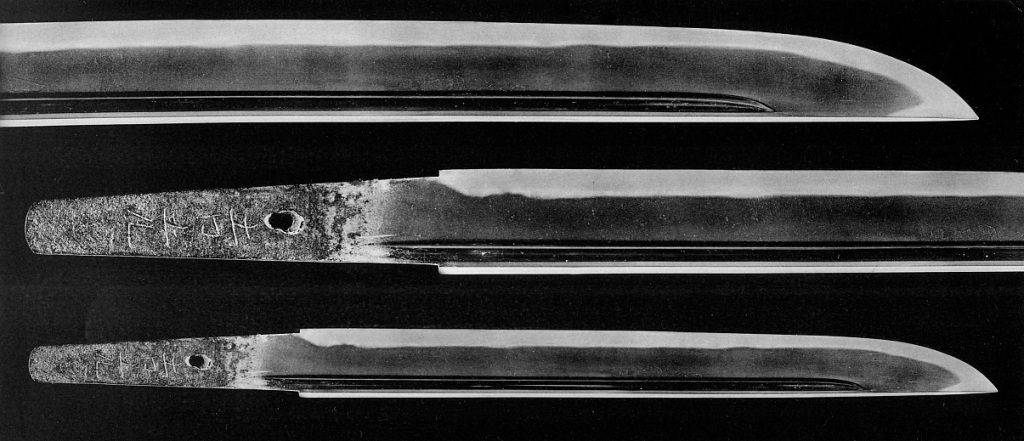

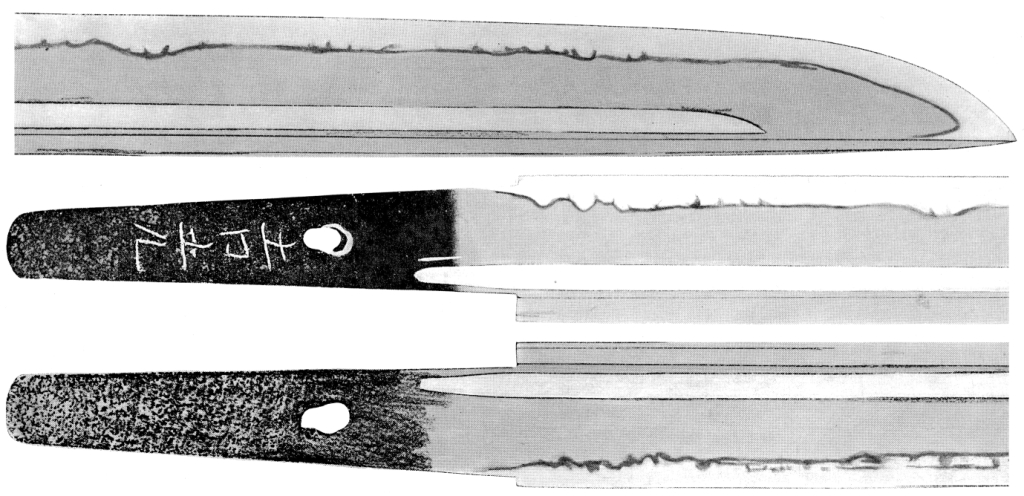

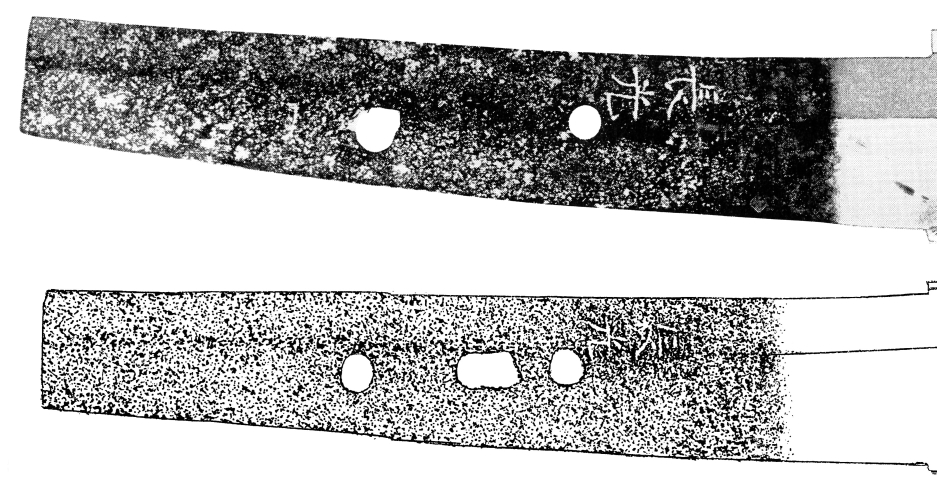

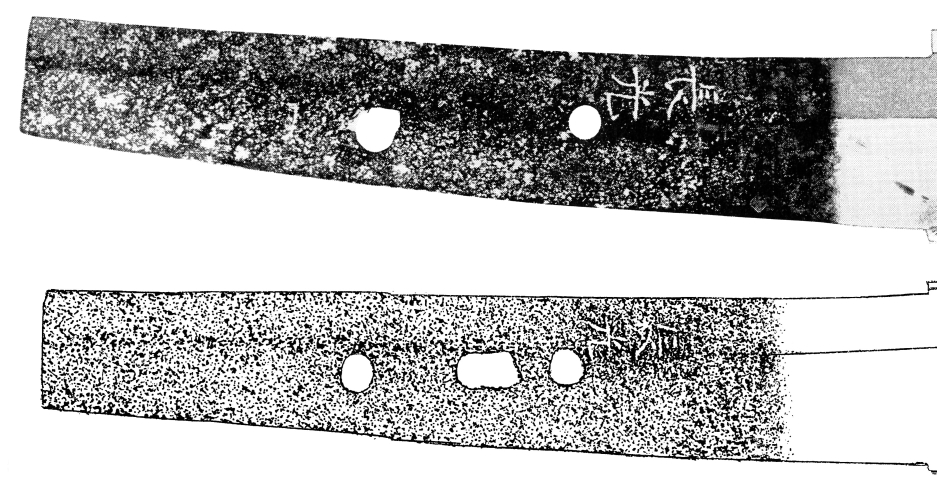

As a transition I want to compare the tang of the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu with the national treasure blade Daihannya-Nagamitsu (大般若長光) which is the subject of the next episode. Depicted on the next page (see picture below) one can see the identical position of the signature as well as of the uppermost, original mekugi-ana.

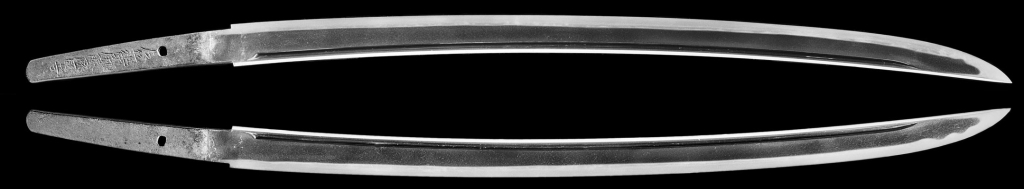

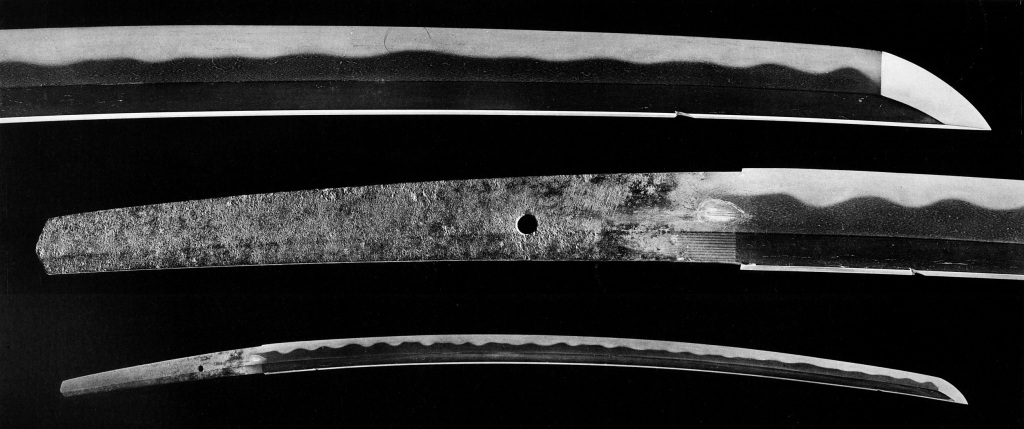

kokuhō Daihannya-Nagamitsu, mei: “Nagamitsu,” nagasa 73.6 cm, sori 2.9 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, deep koshizori, funbari, broad mihaba, ikubi-kissaki, ubu-nakago at which only the very tip of the tang was altered slightly

kokuhō Daihannya-Nagamitsu, mei: “Nagamitsu,” nagasa 73.6 cm, sori 2.9 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, deep koshizori, funbari, broad mihaba, ikubi-kissaki, ubu-nakago at which only the very tip of the tang was altered slightly

Tang of the Daihannya-Nagamitsu top and of the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu bottom. Please note the matching position of the signature and the uppermost mekugi-ana.

Tang of the Daihannya-Nagamitsu top and of the Kannagiri-Nagamitsu bottom. Please note the matching position of the signature and the uppermost mekugi-ana.

The Daihannya-Nagamitsu appears in historical records the first time when it went from the 13th Ashikaga-shōgun Yoshiteru to Miyoshi Nagayoshi ging (三好長慶, 1523-1564, his first name can also be read as Chōkei). The balance of power of late Sengoku-period Japan were far away from being settled and when Yoshiteru was installed as shōgun in Tenbun 15 Tenbun (天文, 1546) after the forced abdication of his father Yoshiharu (義晴, 1511-1550), he was with eleven years de facto under control of the regent (kanrei, 管領) Hosokawa Harumoto (細川晴元, 1514-1563). All these actions took place outside of Kyōto but later Yoshiharu conclude agreements with the Hosokawa regent that he was allowed to return to Kyōto where the Ashikaga shōgun had ruled before. So far so good but Miyoshi Nagayoshi – actually a vassal of Hosokawa Harumoto – switched sides and deserted to of Yoshiharu´s enemies. As a result new fightings broke out, Miyoshi was victorious but spared Yoshiharu´s life with the intention that he was now in control of the then shōgun instead of Harumoto. So it is likely that the sword came into the possession of Miyoshi Nagayoshi in the course of this new distribution of power.

Later the sword came to Oda Nobunaga, probably when the Miyoshi family was driven out of Kyōto in 1568. At the Battle of Anegawa (Anegawa no tatakai, 姉川の戦い) which took place two years later, it was Tokugawa Ieayu who distinguished himself and so Nobunaga rewarded him with the Daihannya-Nagamitsu. In 1575 there were new fightings, this time around the besieged castle of Nagashino (Nagashino no tatakai, 長篠の戦い), which was held successfully against the outnumbering Takeda army by the then only twenty year old Okudaira Sadamasa (奥平貞昌, 1555-1615) – a retainer and son-in-law of Ieyasu. For this glorious act which contributed to the victory of Nobunaga and Ieyasu he received from the latter the Daihannya-Nagamitsu and Oda Nobunaga allowed him to use the character „Nobu“ of his name whereupon Sadamasa changed his name to Nobumasa (信昌).

Nobumasa passed on the sword to his fourth son Tadamasa (忠明, 1583-1644). Tadamasa´s mother was a daughter of Ieyasu and when he was adopted 1588 into the Tokugawa family, he received the family name Matsudaira (松平), the former family name of Ieyasu before he used the name Tokugawa. Later the sword was transferred to this Matsudaira branch which was in control of the Oshi fief (忍) in Musashi province. But for financial reasons the Matsudaira had to part from certain pieces of the family property in the Taishō era (大正, 1912-1926), among them the Daihannya-Nagamitsu. It was bought by the politician and statesman Count Itō Miyoji (伊東巳代治, 1857-1934). After the death of the latter it was once more auctioned off by the relatives and bid when to the Imperial Museum (Teishitsu Hakubutsukan, 帝室 博物館) – the present-day Tōkyō National Museum – for the then unbelievable high price of 50.000 Yen. In 1951 the sword received the status of a national treasure. Of course there was a lot of talk about the price the museum paid but it was originally a price too which gave the sword the nickname Daihannya.

It all started with the daizuke (代付) called practice that from the late Muromachi period onwards, a certain monetary value was assigned to smiths and their works. The publishing of such lists was of course connected to the sword presents mentioned in the last chapter and helpet to weigh which sword could be presented to whom and on which occasion. Blades received origami papers from the Hon´ami family, the official sword appraisers of the Shōgunate, and there was a separate list for swordsmiths how much their blades are worth. Such an assessment list was the Shokoku Kaji Daizuke no Koto (諸国鍛冶代付の事, “Assessment of Swordsmith from the Various Provinces”) published in the 19th year of Tenshō (天正, 1591). In this work blades by Sanjō Munechika, Awataguchi Tōshirō Yoshimitsu (粟田口藤四郎吉光), Awataguchi Kunitsuna, and Bungo Yukihira were valued with 100 kan, followed by Masamune with 50 kan, and Sōshū Sadamune (相州貞宗) with 30 kan. For the Daihannya-Nagamitsu, the unbeliavable value of 600 kan (in Japanese pronounced as roppyaku-kan, 六百貫) was estimated! Because this value was so unrealistic it was jokingly compared with the 600 volumes of the “Large Sūtra on the Perfection of Wisdom” (Daihannya-kei, 大般若経) because “600 volumes” reads also as roppyaku-kan. And so the blade got its nickname Daihannya. This shows how important the holding of Nagashino Castle was for Ieyasu that he rewarded Nobumasa with this most valuable blade.

—————

*1 Today, Katada is not longer an independent village but was 1967 incorporated to the city of Ōtsu (大津).

*2 This was not a plane with wooden chest and slanting cutting edge but a so-called yari-kanna (槍鉋, lit. “spear plane”) which is – as the name suggests – shaped like a spear. It is used with carving movements to plane wood.

*3 The Ōmi-based branch of the Minamoto family bore also the family name Sasaki (佐々木). Later this branch was split up into four further branch families: the Rokkaku, Kyōgoku (京極), Ōhara (大原), and Takashima (高島). So the Rokkaku family is sometimes also referred to as Sasaki-Rokkaku family.